One day, you are suddenly thrust into a series of death games in which you have to outfight and outsmart your fellow competitors. None of you really know how you got here, and no one really understands why you have to kill each other, but a voice in the sky/your faceless dystopian government/the masked agents of a mysterious, evil organization are forcing you to murder other human beings that you’ve never met before in your life. None of this makes sense. You are about to die.

“But wait,” you say, straightening up from your battle-ready posture. “I know this story. Isn’t this just the plot of Battle Royale/Squid Game/The Hunger Games/Alice in Borderland? This is derivative.”

“Is it?” says unlimited flow. It pauses to consider this for a moment. “I don’t think I particularly care.”

Before you can retort, it has sicced the literal dinosaurs of Jurassic Park1 on you.

As someone who grew up on Tolkien and McCaffrey, cut their teeth on the usual SF/F culprits, I like to think that I am fairly proficient in contemporary genre fiction. And yet last year, while browsing my preferred webnovel platforms, I kept running into an unfamiliar category: 无限流. Searching in English only informed me that this genre is apparently so obscure in Anglophone spaces that it doesn’t even have a Wikipedia page. A quick search in Chinese turned up the following:

无限流意义应该是“包罗万象”,即:包含无限元素,包括科学、宗教、神话、传说、历史、现实、电影、动漫、游戏等,并且高于它们,有这样包含这一切的世界观才是无限流小说的精华。但部分无限流小说只是单纯模仿无限三部曲的“形”,而忽视了它的“神”。

The meaning of unlimited flow should be “all embracing;” i.e., it contains unlimited elements, including science, religion, myth, legend, history, reality, film, animation and comics, video games, etc, and is higher than them. This is the essence and brilliance of unlimited flow—a worldview that contains all of this. But some unlimited flow novels only imitate the “form” of the Unlimited Trilogy, while overlooking its “divinity2.”—百度百科 Baidu Baike, “无限流 (小说流派)” / “Unlimited Flow (fiction genre)3”

Already, this definition raises questions and invites speculation: how can a book attempt to include all that and not topple over from its own bloatedness? What does it mean for a work to be “higher” than the elements that compose it? What is the Unlimited Trilogy, and why is its “divinity” so elusive? What does an unlimited flow novel even look like, given that this definition is so broad that it’s practically meaningless?

There was nothing for it. I rolled my sleeves up. I dove in.

What I’ve gathered so far…

无限流 wuxian liu, which I prefer to translate as “unlimited flow,” isn’t so much “unlimited flow” as it is “novels in the Unlimited style” (the characters form a portmanteau of 无限 wuxian / “unlimited” and 流派 liupai / “genre, style”). Here, Unlimited refers to the partial trilogy of 《无限恐怖》 Unlimited Horror, 《无限未来》 Unlimited Future (never finished), and 《无限曙光》 Unlimited Dawn, written by the webnovelist 张恒 Zhang Heng under the penname zhttty. In 2007, zhttty began serializing Unlimited Horror on the Chinese webnovel platform 奇点 Qidian, and the massive popularity of the work inspired a surge of imitators. The protagonist of Unlimited Horror, Zheng Zha4, enters an alternative space under the control of an omnipotent 主神 “Prime God” where he must survive immersion in an unending stream of horror films. Unlimited Horror draws upon well-known and well-loved classic movies, flinging Zheng Zha into films such as Jurassic Park, Resident Evil, and A Nightmare on Elm Street.

While derivative genres like fanfiction and transmigration/isekai stories were already common, even over-played at the time, Unlimited Horror broke new ground by daring to incorporate so many existing texts into its increasingly sprawling playground of imagination5. It manages to cohere all of these disparate influences under the auspices of the “Prime God”—all-powerful and all-encompassing, the Prime God can make anything happen in its alternative space, thereby sidestepping any bothersome questions of worldbuilding. Why the dinosaurs from Jurassic Park? Because the Prime God decided so. Why Freddy Krueger? Because the Prime God decided so. How can all of these even exist in one place? Because the Prime God decided so, and also appears to be a fan of these particular movies.

And so, the original meaning of 无限流 was this—works written imitating the format and style of zhttty’s Unlimited trilogy. As other authors sought to imitate and innovate upon this newly-identified form, tropes and twists of worldbuilding came in and out of vogue. The emergence of the subgenre 数据无限流 “data unlimited flow” pioneered the gamification of the genre, turning the narrative from a protagonist surviving various horror films to a protagonist fighting through the levels of a video game-esque world. But even if the trappings and details of particular iterations of unlimited flow changed, two things remained constant: the protagonist’s struggle to survive in a senseless world, and the merciless, bloody-minded entity that put them through these deadly trials.

It should be noted that unlimited flow is not exactly a new genre, nor was it invented wholesale by zhttty in 2007 with Unlimited Horror. Rather, Unlimited Horror crystallized and named the genre—at least in Chinese-language spaces. One could point to forerunners of unlimited flow in works such as the 2000-2013 Japanese manga GANTZ (in which two high schoolers, after dying, are forced to execute missions for a mysterious black sphere) or the 1997 Canadian film series Cube (in which characters are inexplicably transported into a labyrinthine cubical death trap they must escape or die trying). Nevertheless, the naming and distillation of the genre through Unlimited Horror in 2007 marked a watershed moment in its history. After 2007, these odd, genre-bending works of horror-dystopian-grimdark-cyberpunk-survival-social satire-metafiction-speculative fiction-death games were no longer isolated works, but part of a larger body of literature and media.

Genre Overview

As far as I can gather from the texts I’ve read so far, unlimited flow works generally contain the following:

- a breakage from reality: something occurs that forcibly jolts the protagonist—and possibly the entire world along with them—out of their otherwise unremarkable daily routine. Often, but not always, this is the end of the world.

- a system: the system is usually the agent of the breakage, and possesses god-like powers to remake and reshape reality. Crucially, the system is unfeeling and uncaring—it imposes the end of the world as we know it and the beginning of a new world order, usually through violence. It cannot be reasoned with, and it does not show mercy. Note that the system is not always an explicit, embodied entity; sometimes, its existence remains implied, sublimated into the worldbuilding.

- iterative death games/missions/scenarios: the protagonist(s) must survive/successfully fulfill the tasks given to them by the system, or else perish. Completing games/missions often helps characters gain important knowledge, skills, power-ups, or items while proving their worthiness to the system. These iterative death games/missions/scenarios often riff on familiar genre plots, tropes, or experiences. For example, 《地球上线》 The Earth is Online finds endless joy in making childhood games like hopscotch or carnival games like whack-a-mole incredibly lethal for the player. 《薄雾【无限】》 Mist [Unlimited] takes its readers on a tour of a zombie apocalypse, a deadly labyrinth, and commonly-seen time travel tropes such as time loops, parallel universes, and time dilation. 《全球高考》 Global University Entrance Examination borrows the framework of the Chinese gaokao exam to drop its characters into a Last Supper-themed hunting lodge (physics), a haunted village (foreign language), and an ill-fated trading expedition trapped in the Arctic (history), among others. Rather than be ashamed by how derivative its components can be, unlimited flow gleefully blends elements across time, space, history, myth, religion, science, fiction, and media in a giant crockpot of general mayhem.

Some common themes in unlimited flow include:

- violence, and the uglier side of human nature: many unlimited flow novels are dark, bloody, and violent—likely influenced by the genre’s strong affinity to horror. Often, one of the first scenarios is one that requires characters to do violence to another person in order to survive, emphasizing that the rules and principles that may have governed the old world (morality, compassion, righteousness) are no longer relevant. The apocalyptic nature of many unlimited flow novels is emphasized when the collapse of societal order brought about by the system results in people taking advantage of the chaos in despicable, crude, and exploitative ways.

- trust, friendship, and loyalty: arising naturally out of the new, violent chaos of a broken world is the importance of finding people you can trust. Often, unlimited flow novels focus on the slow acquisition of team members, winnowing out inferior or untrustworthy hangers-on, and eventually, trusting your companions with your life.

- gaming the system, and eventually, overcoming the system: as your protagonist(s) steadily advance(s) through the iterative scenarios imposed by the system, they begin to learn more about the system and its rules, the loopholes that can be exploited, the blue-and-orange axis of its morality, the origins of the system, and its overarching purpose. This allows the protagonist, who achieves power by continually triumphing within the system, to eventually break the system and liberate the other people trapped in the endless cycle of death games. In a sense, the fantasy that drives many unlimited flow stories is the alluring prospect of succeeding so well within the system that you can amass the raw power to remake it, essentially beating the system at its own (death) game.

Unlimited flow bears strong resemblance to another popular East Asian webnovel genre, isekai. Often categorized as a subgenre of portal fantasy, isekai features protagonists that transmigrate into another world or time period. Protagonists must successfully navigate this new world, usually assisted by their knowledge of the source book/plot/game/time period, in order to achieve their happily ever afters and/or return to their proper worldline. Unlimited flow differs from isekai in that unlimited flow does not always require a character to move from one distinct world/time to another; rather, the reality that is fractured by the system is often the protagonist’s home reality. Isekai often transmigrates the protagonist into the body of an existing character/person, whereas unlimited flow protagonists travel through their narrative in their own bodies. Much of isekai focuses on the protagonist’s struggle to roleplay their vessel correctly, and as a genre, it frequently engages with themes of identity, role, purpose, and destiny. Isekai systems, in turn, are often comedic plot devices, taking a backseat to the worldbuilding of the text it oversees. Where isekais are usually preoccupied with the journeys characters go on as they explore and integrate into a new world, unlimited flow is primarily concerned with survival6.

A Word on Research and Theory

Before we proceed any further, I feel the need to get a few disclaimers off my chest. The first is that I can only read Chinese, which significantly limits my ability to read unlimited flow and texts about unlimited flow in Korean and Japanese—and unlimited flow is a genre popular across all of East Asia, so I am likely missing crucial components of history or influence7. The second is that I am drawing my conclusions based primarily on the unlimited flow novels I have read over the past year, which necessarily biases my conclusions towards the renditions of unlimited flow in those texts8. Additionally, my tastes lean towards danmei, which in and of itself creates an interesting chemical reaction when fused with unlimited flow9. The frog-in-the-well folly of attempting a genre study with only a few texts under my belt is not lost on me, but likewise, the existence of the Dunning-Krueger curve warns me off of chasing some elusive standard of “well-read enough” to talk about the webnovels I spend an ungodly amount of time reading.

Also, I read some really cool books and wanted to yell about them on the internet.

Next, I should clarify what I mean by a “genre study.” Countless centuries of ink have been spilled hairsplitting the borders of genre—who decides which text can be considered which genre, which book gets to be the ultimate ur-text of a genre, which text originated which genre, what standards or elements dictate the boundaries of a genre… Though the film classes I took in college did not culminate in a film degree, they did gift me one of my favorite theoretical frameworks. This form of genre theory, as articulated in the writings of John Frow and Andrew Tudor, argues that, well, genres are fake and don’t actually exist. That is, genres exist as convenient shorthands for us to communicate information about a text to others. They are buckets that allow us to broadly categorize texts with similarities for comparison, but the bucket is a metaphor, and its walls are imaginary and thereby quite porous. In Andrew Tudor’s words, “[g]enre is what we collectively believe it to be.”10

Since genres, then, can be considered collective hallucinations, there is no single arbiter of where the borders of any given genre ought to be. The more fruitful discussion, I’ve found, lies in what additional insights we can gain from reading a text as a certain genre. What could we learn from reading, say, Star Wars as samurai film? How might analyzing Star Wars in the tradition of samurai film inform us about its context and themes? And—coming back to unlimited flow—what might we gain by conceptualizing and contextualizing a genre called unlimited flow?

Fine, let’s talk about Squid Game

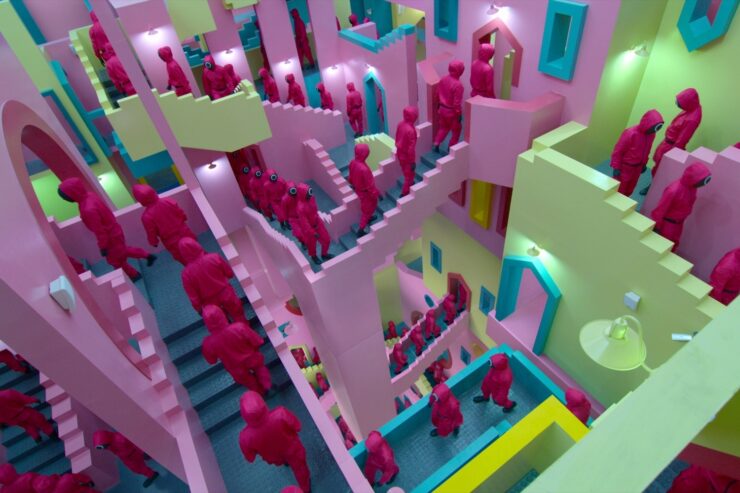

With this broad overview of unlimited flow and oversimplified speedrun of genre theory at hand, let’s apply them to an initial case study. It would not be an exaggeration to say that in the fall of 2021, the South Korean television series Squid Game took the world by storm. Over the course of nine harrowing, nail-biting episodes, Squid Game creates a garish, nightmarish parody of reality TV challenges as financially-stricken players vie against each other in deadly variations of children’s games for a life-altering cash prize. Much has been written about the show’s scathing critique of predatory capitalist practices, socioeconomic inequality, and class struggle, but less has been written on its genre. Different sources categorize Squid Game as science fiction, horror, thriller, or survival.

Iterated death games? Check. Violence, mistrust, and the uglier side of human nature? Check. An all-powerful “system” (as manifested in masked, gun-wielding enforcers) that drives players to kill each other? Check.

Is Squid Game unlimited flow? Both yes and no—Squid Game shares unlimited flow’s most distinctive narrative pattern of iterated death games. Visually, the impossibility of its scenarios (how and why can these death traps and disturbing funhouse rooms even exist? What utterly unhinged building contractor is building these sets, and how can we revoke their license?) mirrors unlimited flow’s tendency to declare that “these are the rules of the scenario, realism and logistics and physics be damned.” And the all-powerful system forcing players to commit violence against each other is none other than capitalism and the oppression of wealth inequality.

That being said, Squid Game isn’t quite unlimited flow because it is actually quite limited—to a familiar world. There is no breakage of reality that moves the narrative from the realm of realistic drama to speculative fiction (which, in and of itself, is the true horror of Squid Game—that all of this is possible). There is no god-system visiting its impassive cruelties upon hapless players—just human cruelties, magnified by money and exploitation. Squid Game isn’t precisely speculative fiction, whereas unlimited flow is firmly speculative, fantastical, futuristic, impossible.

I am uninterested in definitively arbitrating the borders of genre—the greater insight, I believe, comes from seeing what we can learn from contextualizing Squid Game within unlimited flow. By situating Squid Game in a wider tradition of other unlimited flow narratives, it can be compared and analyzed intertextually against works such as 《幸存者偏差【无限】》 Survivorship Bias [Unlimited] (the iterated death game system as a form of extreme late-stage capitalism) or 《地球上线》 The Earth is Online (ruining your childhood memories, one playground game at a time). I personally would consider Squid Game a kind of “low unlimited flow” in the same vein as “low fantasy,” in that both subgenres incorporate typically “high genre” elements into our otherwise familiar world.

I said that I read some cool books, so now I’m going to make that your problem

[Note that the following title-specific sections contain general spoilers for each novel, as the slow reveal of the truth behind the worldbuilding in unlimited flow is often a major component of the plot.]

The Earth Is Online

《地球上线》 The Earth is Online is an unlimited flow danmei webnovel written by 莫晨欢 Mo Chen Huan, serialized from 2017 to 2018. The novel begins with countless black towers materializing in Earth’s atmosphere across the globe, hovering ominously above major urban centers. No scientist can explain their existence; no government can account for their appearance. Gradually, people get used to the mysterious floating black towers and carry on with their lives—school, work, taxes, bills. Six months later, a crisp announcement rings out across the world: ding-dong! On November 15, 2017, the earth is now online. The entire population of Earth is plunged into a series of deadly games, often presided over by familiar fairy tale figures or beloved cartoon characters. Cinderella hosts a trivia show where the consequences of answering incorrectly are often grisly; Snow White hunts players through her moonlit woods at night and terrorizes her dwarves; Mario watches benevolently over a life-sized fusion of Monopoly meets Chutes & Ladders involving duels to the death. Amidst the chaos, unassuming librarian Tang Mo joins forces with lieutenant commander Fu Wenduo to beat the games and attack the seven levels of the black towers, eventually unlocking the secret of why the black towers descended upon Earth in the first place.

The Earth is Online is pure, straightforward unlimited flow. An all-powerful system appears one day and forces all of humanity into iterative death games. Tang Mo and Fu Wenduo team up to clear games, gather information, obtain valuable items, and level up their abilities. Along the way, they are variously helped and hindered by a vibrant cast of supporting characters such as Fu Wensheng (Fu Wenduo’s younger cousin and party healer), Chen Shanshan (a precocious middle school girl with a powerful intellect), Mu Huixue (an enigmatic “returner” who is too powerful even for the black towers), and Bai Ruoyao (a charming and aggravating psychopath with mysterious ties to the seventh level of the black tower). The book gives equal focus to the violent and brutish side of human nature, as the early games incite players to turn on each other, as well as the strength and power of teamwork and community, as the seventh level of the black tower requires the concerted efforts of everyone left on Earth. As mind-bending puzzles and absurd scenarios test the nerve and cleverness of all players, the trial of the black towers forces all of humanity to reckon with the terrible price of survival as they struggle to prove their worth to the cosmos.

Mist [Unlimited]

《薄雾【无限】》 Mist [Unlimited] is an unlimited flow danmei webnovel written by 微风几许 Wei Feng Ji Xu, serialized in 2020. Set in a nebulous, science fictional future, Mist [Unlimited] follows Tianqiong time agent Ji Yushi as he is seconded to the elite Team Seven as their recorder. While the team is initially skeptical of Ji Yushi’s capabilities, he quickly proves his worth as their first mission goes sideways. Hijacked by a rogue version of the Tianqiong AI that normally guides their missions, Team Seven is dropped into a parallel universe ravaged by a zombie apocalypse. A time anchor tethers them to the initial point of hijacking, so Team Seven fights, dies, and loops until they succeed in discovering the source—and solution—of the zombie apocalypse. Teams that survive time loops together stay together, and Ji Yushi’s hyperthymesia—a condition that renders him incapable of forgetting anything he has ever experienced or encountered—proves a crucial asset as Team Seven goes on to accomplish further missions at the behest of the rogue Tianqiong AI.

In this case, the deadly scenarios of unlimited flow manifest in the various missions Team Seven must complete in order to return home to their original timeline: solving and breaking free from nested time loops in a zombie apocalypse; exploring the haunting wreckage of a trash heap in the cracks between timelines; bursting the bubble of an impossible parallel universe; resolving temporal inconsistencies by solving a five-dimensional Rubik’s cube from the inside11. The breakage of their reality occurs when the Tianqiong AI hijacks their time jump, pinning them to a single moment in time with the trans-temporally prohibited technology of a time anchor. Correspondingly, the all-powerful god-system in Mist [Unlimited] is the Tianqiong AI itself, which has attained sentience after transcending its timeline of origin.

Mist [Unlimited] is somewhat unusual among unlimited flow novels in that the protagonists, after unearthing the origins and intentions of the system that subjected them to so much suffering in the first place, do not destroy or overthrow the system, choosing instead to trust the benevolent intentions of the AI’s central directive and its mysterious creator. In addition, the cast of Mist [Unlimited] is relatively small; in contrast to The Earth is Online, where the entirety of Earth’s population is forced into the trial of the black towers, the breakage of reality in Mist [Unlimited] is confined primarily to Team Seven12. Rather than linger on unlimited flow’s usual staples of violence, horror, and the darker side of human nature, Mist [Unlimited] explores instead time, memory, grief, and identity. For Ji Yushi—biologically incapable of forgetting, eternally frozen in the grief of his father’s murder seventeen years ago—the temptations offered by time travel are treacherously destructive. The iterative scenarios not only test the skill and mettle of Team Seven, but also Ji Yushi’s resolve to learn the truth of his father’s murder without changing the past and damaging the timeline. Team Seven’s captain, Song Qinglan, comes to function as Ji Yushi’s emotional anchor, tethering him to the present just as the time anchor tethers them throughout time13. Mist [Unlimited]’s atypicalities show that unlimited flow continues to grow and evolve as a genre as new authors try their hands at innovating upon the framework offered by the combination of system and deadly missions.

Omniscient Reader’s Viewpoint

전지적 독자 시점 Omniscient Reader’s Viewpoint is an unlimited flow webnovel serialized from 2018-2020 by the married author duo 싱숑 Sing Shong14. One day, on the subway home from work, ordinary salaryman Kim Dokja is isekaied into his favorite webnovel, except that Kim Dokja is no ordinary salaryman, Three Ways to Survive in a Ruined World is no ordinary webnovel, and this is not your ordinary isekai narrative. The world is plunged into a cutthroat competition in which humans are required to complete scenarios in order to survive and earn their keep in the universe-spanning Star Stream. In an uncanny mirror to certain corners of the internet, the Star Stream is an entertainment and livestream platform where celestial beings known as Constellations tune into channels, live-react into chat boxes, and sponsor humans (“Incarnations”) with coins, items, and abilities (“Stigmas”). As Kim Dokja utilizes his knowledge of Three Ways to Survive in a Ruined World to battle his way through the subway systems of Seoul15, he gathers trustworthy companions and important items alike to aid him in his ultimate mission—the destruction of the voyeuristic, exploitative Star Stream itself.

But Kim Dokja is not the only player on the board: Yoo Joonghyuk, the gifted protagonist of Three Ways to Survive in a Ruined World, blazes through the scenarios in a path of glory, gore, and violence. Yoo Joonghyuk is a regressor—a man with the Constellation-sponsored Stigma to rewind the scenarios and restart from the beginning—and his endless speedruns of the scenarios push him closer and closer to madness with every iteration of tragedy he endures. But this regression is different from all of his previous ones: never before has the infuriating and cryptic Kim Dokja appeared in any of Yoo Joonghyuk’s past regressions. And if Kim Dokja, this mysterious, charismatic, self-sacrificing idiot can be trusted, this regression might just be Yoo Joonghyuk’s last one16.

Omniscient Reader’s Viewpoint tricks you into thinking that it’s an isekai novel for a few hundred chapters, and by the time you’ve cottoned on, it’s too late—you, and the characters, have much bigger things to be worrying about. Due to the book’s clever genre-within-a-genre structure (an unlimited flow novel masquerading as an isekai novel about transmigrating into an unlimited flow novel), Omniscient Reader’s Viewpoint actually has two systems: the oppressive, omnipresent Star Stream that oversees the deadly scenarios and a “meta-system” of the book’s narrative itself, arcing towards an inevitable, pre-written ending. The book’s official final chapter is chapter 516, but in true unlimited flow fashion, Kim Dokja’s Company17 fights to change that ending in an additional 35 chapters of epilogue, refusing to accept an ending to their story that they are not satisfied with18.

If the problem with most unlimited flow these days is that they merely imitate the “form” of Unlimited Horror and ignore its “divinity,” Omniscient Reader’s Viewpoint is a strong contender for heir to that divine throne. Sing Shong skillfully and lovingly melds isekai and unlimited flow as the protagonist and his reader work together to dismantle the torturous cyclical narrative of regression that keeps Yoo Joonghyuk trapped in an eternity of repetitions. In the all-encompassing, all-embracing spirit of unlimited flow, Omniscient Reader’s Viewpoint features a cast of gods and monsters, demons and deities alike. National folk heroes and mythical beings crowd into channels to ogle the struggle of human incarnations from on high. As they progress through the scenarios, Kim Dokja’s Company re-enacts and reclaims legendary battles and destruction myths, from the ancient Greek Gigantomachia to the apocalyptic biblical Revelations, even riffing on the Chinese classic Journey to the West. In the world of the Star Stream, stories are food, currency, weapons, power; they are the fundamental building blocks of people, communication, the entire universe, and more. And while the Star Stream itself embodies a cruel, voyeuristic mode of storytelling—exploiting the suffering and tragedy of human Incarnations for the amusement of the stars—storytelling remains the only way anyone can truly communicate with and reach one another.

Omniscient Reader’s Viewpoint is a love letter to all readers and the books they love, even if—or especially if—the book is a trashy, overlong webnovel about a dauntless protagonist battling his way through endless iterative death game scenarios19. The love a reader has for a book, the world, and the characters within it, Omniscient Reader’s Viewpoint argues, is a force powerful enough to save lives and rewrite the structure of reality.

Okay, great, now what?

So why read unlimited flow? Why care about it? Why go to all the trouble of trying to classify yet another genre in this day and age of having more media, more stories, more reading material than ever before to drown ourselves in? Why, in short, should we care about unlimited flow and whether or not it exists?

Personally, I don’t particularly enjoy the death game/survival genre, but observing the popularity of unlimited flow made me deeply curious as to what fans of the genre found so compelling. I wanted to know what was in the water here. And amidst the death and the carnage, the uncaring systems and the carcasses of worlds, I found a form of genre fiction unique to the 21st century.

Unlimited flow defies the traditional expectations of worldbuilding as we’re used to seeing them in science fiction and fantasy. If conventional worldbuilding wisdom asks us to make magic and spaceships properly believable, requiring authors to diligently analyze how the presence of a particular form of magic or a critical technological development may affect characters, society, and the ways of life in that world, then unlimited flow simply does not care. In the words of tumblr user neuxue, unlimited flow’s main priority is to “pu[t] these guys in Situations,” practicality or plausibility be damned. As a result, unlimited flow protagonists can have it all—superpowers bestowed by the system (The Earth is Online), time travel technology beyond the capabilities of their futuristic era (Mist [Unlimited]), even a seven-chapter medieval fantasy AU in which the characters must choose the genre of the narrative and rewrite the story to succeed (Omniscient Reader’s Viewpoint)20. How can this happen? How is any of this possible? Unlimited flow does not care; it simply tells you what the new rules of the world are, and you must adapt to survive.

Protagonists may cycle in and out, aesthetics come in and out of vogue, but the focal point, the bearing wall, the gravity well of unlimited flow remains the system. Inciting incident, narrative framework, and antagonist all in one, the system is cruel and merciless. It cannot be reasoned with. In the 21st century, as we face more pressures than ever from giant, faceless forces that change and shape the world, we can see the shadow of unlimited flow systems in the ebb and flow of capital, in exploitative neoimperialist policies, in the cheapening and commodification of tragedies and atrocities, in authoritarian governments censoring and oppressing their own people. Unlimited flow stands adjacent to apocalyptic and dystopian fiction for good reason; unlimited flow rehearses the chaos of societal collapse and plays through the rise of a world order subservient only to power. Under the governance of the system, only those who are powerful can protect themselves, and only when you can protect yourself do you have the luxury of kindness and compassion.

It is no wonder, then, that so many unlimited flow protagonists appear so unassuming and ordinary on the surface—Tang Mo the librarian, Kim Dokja the salaryman. The collapse of society is what allows them to excel and succeed far beyond what the previous world order—our current one—would have allowed. Before, they would have crowded onto buses, vanished into anonymous crowds on the subway; now, they can become heroes, legends, constellations in the night sky. Unlimited flow presents the fantasy that some ordinary guy can become the savior of the world, often precisely because of an otherwise unvalued skill—proficiency in video games, perhaps, or in Kim Dokja’s case, an obsession with reading mediocre webnovels. Though the worldbuilding, narrative tropes, and thematic focus of unlimited flow inclines the genre towards power-up fantasies and mindless worship of might, many unlimited flow stories also highlight the value and nobility of doing good in a world gone mad. Like any good dystopian novel, unlimited flow texts search for and treasure what fragments of humanity can be preserved and expressed in hellish times. Unlimited flow firmly believes in the hope for a better future and exalts the battle to create one in defiance of the strictures of the system.

Beneath the titillating violence and horror of unlimited flow lies a uniquely modern existential dread: surrounded as we are by systems that render us complicit in violence to other people, how should we survive and fight back? The endless iterations of deadly scenarios and impossible missions in unlimited flow are dramatized, magnified, genre-fied versions of our daily struggles to work, to make a living, to survive another day within the systems that govern our lives. Perhaps it is no accident that unlimited flow flourished specifically in the medium of serialized webnovels; one need only imagine how many readers pass their hours of commute jostling on the subway, head bowed over their phones, witnessing unlimited flow protagonists forging forward in their insane, impossible, unsurvivable worlds. At its core, unlimited flow is a genre about surviving in a world that strives to kill you and the unquestionable nobility of the fight to break free from senselessly cruel systems. Unlimited flow is a genre that is unrepentantly alive; never once does the genre or its protagonists consider if it would be better to simply lie down and give up. Unapologetically, unequivocally, the impetus of unlimited flow is towards life, towards survival, towards fighting for the opportunity to (re)build a better world than the one we’re trapped in now.

So… where were we?

You collapse, exhausted, onto a broken concrete block. Letting out a long exhale, you lean back on shaky arms and stare up at a sky streaked in apocalyptic hues of red and gray. Thick plumes of smoke spiral lazily upwards from the smoldering wreckage in the distance, which you may or may not have had a hand in setting on fire. “So,” you say, at the end of everything. “What happens now?”

Unlimited flow comes to settle beside you, perching on a nearby rusty pipe that must have been unearthed in the destruction. It looks at you with deep, fathomless eyes that flicker with the data of a thousand systems, with the darkness of unnumbered deaths. “What do you think?” it asks.

“Well,” you say. “If that explosion took down the system for good, then we’re free. We can finally have our happy ending.”

Unlimited flow hums, noncommittal.

“But if the system somehow escaped our trap,” you say, “then there will be more work to do. More battles to fight.”

Unlimited flow nods. “Mhm.”

You resist the urge to grab the genre by the shoulders and shake it vigorously. Then what was the point of all this? you want to yell. What was the point of all this senseless violence and bloodshed and carnage and gore? What was the purpose of all this voyeuristic suffering, the futile struggles, the immense sacrifices, the countless hours poured into reading chapter after chapter of worlds on fire, worlds gone mad? Instead, it comes out quiet. “Why did it have to happen like this?” you say, gesturing around you at the broken land, the desolate sky, the bones and bodies moldering beneath your feet.

Unlimited flow gives you a look.

“What?” you say, a bit injured.

Unlimited flow scrubs a hand over its face before turning to you. “Did you journey? Did you change? Did you learn something new? Did you see the great evil in human nature, as well as the great good? Did you come to value trust and companionship, even as you guarded against others who would have stabbed you in the back? Did your heart fall when the protagonist did, and did you steadfastly accompany them as they slowly climbed back to their feet, and to the top? Did you cheer for the triumphs and weep for the sacrifices? Did you rail against an unjust world, against merciless systems? And did you always, always, turn the page and keep reading?

“Having read all of these iterations of desperate battles against the systems, are you now ready to go out and fight your own?”

You reel a bit from the onslaught, then catch the implication. “So it’s not over?”

Unlimited flow shrugs. “This one is,” it says, its dismissive gesture encompassing the ruined landscape around you. “But out there?” It nods at a door that has suddenly appeared out of nowhere. You’ve given up trying to explain the laws of conservation of matter to this universe. This might as well happen too.

The two of you sit there in silence for a bit, letting the words sink in. The door waits, patient and eternal. Behind it, you sense, is the world you will wake up to.

“This is still really derivative,” you say.

“Mhm.”

“And tropey, and absurd.”

“Mhm.”

“And often badly written, logically inconsistent, and full of plot holes,” you say, gaining momentum.

Unlimited flow slants a look at you. “But you read it.”

That takes the wind out of your sails. “I guess.”

You both watch the smoke for a little while longer, and you feel a little curl of something like satisfaction, looking at your work. It’s been a long, long journey of hundreds of chapters to this ending, and even if you may have rolled your eyes frequently, often, with great feeling, the fact that you made it all the way here should still count for something, right?

“So,” unlimited flow says, standing up and dusting its palms off. “Are you ready?”

“Not particularly,” you respond.

Unlimited flow flashes you a quick, feral smile. “Be brave,” it says—and shoves you through the door.

WORKS REFERENCED

Frow, John. “Approaching Genre.” In Genre, 6–28. The New Critical Idiom. London; New York: Routledge, 2006.

观娱象限 Guanyu Xiangxian, “《开端》火了,它能代表无限流吗? Kaiduan huole, ta neng daibiao wuxianliu ma?” 虎嗅 Hu Xiu, last accessed 1/15/24, <https://m.huxiu.com/article/490499.html>

莫晨欢 Mo Chen Huan, 《地球上线》 The Earth is Online. Beijing: 晋江文学城 Jinjiang Literature City, 2017-2018. <https://www.jjwxc.net/onebook.php?novelid=3377217>

木苏里 Mu Su Li, 《全球高考》 Global University Entrance Examination. Beijing: 晋江文学城 Jinjiang Literature City, 2018-2019. <https://www.jjwxc.net/onebook.php?novelid=3419133>

싱숑 Sing Shong, 전지적 독자 시점 Omniscient Reader’s Viewpoint. Seoul: 문피아 Munpia, 2018-2020.<https://novel.munpia.com/104753>

Tudor, Andrew. “Genre.” In Film Genre Reader IV, 3-11. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2012.

微风几许 Wei Feng Ji Xu, 《薄雾【无限】》 Mist [Unlimited]. Beijing: 晋江文学城 Jinjiang Literature City, 2020. <https://www.jjwxc.net/onebook.php?novelid=4357146>

“无限流(小说流派)_百度百科 Wuxianliu (xiaoshuo liupai)_Baidu Baike,” 百度百科 Baidu Baike, accessed 1/15/24, <https://baike.baidu.com/item/%E6%97%A0%E9%99%90%E6%B5%81/5383795>

修行真知 Xiuxing Zhenzhi, “且说无限流与《无限恐怖》 Qieshuo wuxianliu yu Wuxian Kongbu,” 知乎专栏 Zhihu Zhuanlan, accessed 1/15/24, <https://zhuanlan.zhihu.com/p/44315965?utm_id=0>.

阅文起点创作学堂 Yuewen Qidian Chaungzuo Xuetang, “《无限恐怖》解析 Wuxian Kongbu Jiexi,” Yuewen Jituan 阅文集团, accessed 1/15/24, <https://write.qq.com/portal/content?caid=21468604801026301&feedType=1&token=undefined>.

张恒 Zhang Heng, 《无限恐怖》 Unlimited Horror. Shanghai: 起点中文网 Qidian Chinese Web, 2007-2009. <https://book.qidian.com/info/109222/>

稚楚 Zhi Chu, 《幸存者偏差【无限】》 Survivorship Bias [Unlimited]. Beijing: 晋江文学城 Jinjiang Literature City, 2021-2022. <https://www.jjwxc.net/onebook.php?novelid=4200722>

- If I had a nickel for every time Jurassic Park featured in an unlimited flow novel I’ve come across, I’d have two nickels, which isn’t much, but it’s weird that it happened (at least) twice. ↩︎

- I am not convinced that “divinity” is the best translation for 神 shen—alternative translations could be “spirit,” “magic,” or even “soul.” The impression that I get is that 神 shen is evoking that special something that makes unlimited flow really come to life, that spark of genius that lies at the heart of the Unlimited Trilogy. ↩︎

- This definition is sourced from the Baidu Baike page on unlimited flow. Baidu Baike is a collaborative online encyclopedia roughly analogous to a Chinese-language Wikipedia, but it suffers from government censorship and lack of authenticated information sources. As a result, I have no idea where or who this definition of unlimited flow came from, though many of the subsequent articles I found on unlimited flow reference this definition. I have many questions about who wrote this definition, considering how widespread it is, because the last sentence gives off a tantalizingly opaque sense of affrontedness at the number of inferior imitators that merely mimic the “form” of Unlimited Horror. Who are you, mysterious definition writer, and what did you really mean by the “divinity” of the genre? Who are you vagueing, and what was the drama?

All translations from Chinese in this article (and errors as a result) are my own. ↩︎

- Is it a coincidence that 郑吒 Zheng Zha’s name is homophonous with the binome 挣扎 zheng zha “to struggle?” What you do is up to you, but I’m pressing F to doubt. ↩︎

- Unlimited Horror is 823 chapters, or 26,894,000 characters, long. For reference, that’s over ten times the approximate word count of the first half of Brandon Sanderson’s The Stormlight Archive at the time of this article’s writing (#1 – #5, with Wind and Truth estimated at 480k words), or conceivably five times as long as what all ten books of Stormlight may add up to. ↩︎

- It may be worth noting that the line between isekai and unlimited flow is frequently blurred by crossover or fusion texts. Protagonists will isekai into unlimited flow novels/worlds, or unlimited flow novels will feature isekai subplots/death games. In fact, there is a subgenre of isekai known as 快穿 kuaichuan (lit. “speed transmigration”) in which your protagonist isekais into several successive worlds/stories, often aided or forced by a system. In that case, would speed transmigration be considered isekai or unlimited flow, and at the end of the day, does it really matter? ↩︎

- Unlimited flow is also quite popular outside of East Asia as well, but to get into a discussion of that would rapidly escape the scope of this piece. Consider this a “but_we_don’t_have_time_to_unpack_all_that.gif” moment. ↩︎

- For example, I gravitated towards science fiction/video game-inflected unlimited flow, as opposed to fantasy/supernatural or wuxia-leaning unlimited flow. ↩︎

- 耽美 Danmei is a genre of Chinese web literature characterized by its focus on idealized male/male romance. To get into the history, development, and contemporary significance of danmei is far beyond the scope of this already unwieldy discussion about a different genre entirely, but danmei plays a particularly interesting role in the evolution of unlimited flow as a genre. For a more in-depth dive on the history of unlimited flow as it crossed from 男频 nanpin channels to 女频 nvpin spaces, I recommend the article “《开端》火了,它能代表无限流吗?” for anyone who can read Chinese. ↩︎

- The Andrew Tudor quote is from his chapter “Genre” in the Film Genre Reader IV, edited by Barry Keith Grant. The John Frow chapter I have in mind is from his book Genre (The New Critical Idiom), first published in 2005. ↩︎

- Wei Feng Ji Xu specifically noted that the 魔方 “Magic Cube” arc in Mist [Unlimited] was inspired by the Cube films. Such are the benefits of conceptualizing a genre: intertextuality! ↩︎

- At least, for the earlier arcs. The “Magic Cube” arc sees the arrival of multiple teams from various alternate timelines that have all been kidnapped by the sentient system. ↩︎

- Song Qinglan also comes to function as Ji Yushi’s boyfriend. This is, after all, a danmei novel. ↩︎

- Due to translation/transliteration inconsistencies, 싱숑 has been variously rendered as sing-shong, sing-syong, or sing N song depending on which sources you look at. Similarly, the transliteration of the characters’ names has also shifted between various English translations, e.g. Yoo Joonghyuk vs. Yu Jung-Hyeok, Jung Heewon vs. Jeong Hui-Won, Lee Jihye vs. Yi Ji-Hye. I hereby apologize for undoubtedly getting all of them wrong. I went with what Wikipedia had. ↩︎

- They do eventually escape the subway tunnels of Seoul, but the first five scenarios (mostly) take place underground. The subway is a recurring motif in the novel, and the book both begins and ends on the subway. It’s very hard to be normal about the subway after finishing Omniscient Reader’s Viewpoint. ↩︎

- This summary is Han Sooyoung erasure, but also I cannot even begin to explain Han Sooyoung without getting far too deep into Omniscient Reader’s Viewpoint. Instead, I would like to cordially invite you to read this webnovel and weep. ↩︎

- Yes, that is literally what the squad is called—a fact that everyone gives Kim Dokja grief for. ↩︎

- Omniscient Reader’s Viewpoint, at 551 chapters, was completed in February of 2020. In early 2023, Sing Shong returned to the work and began serializing the side story, which picks up, more or less, from the end of Omniscient Reader’s Viewpoint. As of March 2024, the side story has passed the hundred-chapter mark and is projected to go for at least a few hundred more. ↩︎

- Three Ways to Survive in a Ruined World is, canonically, terribly written. This is far more important to the plot than you might expect it to be. ↩︎

- No seriously, this is exactly what happens in the Kaizenix Archipelago arc. A subset of Kim Dokja’s Company is isekaied into the Kaizenix Archipelago, whereupon they continue to do what they do best: subvert narratives, incite revolutions, and generally wreak havoc. ↩︎